Spirit of Eden und Laughing Stock sind Meilensteine. Die beiden letzten beiden Talk Talk-Alben liessen John Lee Hooker und Miles Davis anklingen, Elvin Jones und Ligeti, Robert Johnson und Gil Evans, als Stoff der Verwandlung, als Spurenelement. Und sowohl Mark Hollis wie Tim Friese-Greene hatten einige alte ECM-Platten als Quelle der Inspiration ausgemacht.

Die Entstehung beider Alben ist legendär. Sicher wurden die Grenzen der Belastbarkeit öfter überschritten, bei dem Nachfolger Laughing Stock noch um einiges mehr. Soundmeister Phill Brown erinnert sich an The Spirit Of Eden:

„I recall an endlessly blacked-out studio, an oil projector in the control room, strobe lighting and five 24-track tape-machines synced together. Twelve hours a day in the dark listening to the same six songs for eight months became pretty intense. There was very little communication with musicians who came in to play. They were led to a studio in darkness and a track would be played down the headphones.”

Das letzte Werk von Mark Hollis erschien im Januar 1998, und hiess schlicht Mark Hollis. Es gehört In die einsame Klasse zeitgeistferner Aufnahmen jener Jahre, in dieser Hinsicht vergleichbar mit Robert Wyatts Shleep, Scott Walkers Tilt, Brian Enos Nerve Net. All diesen Alben ist etwas Überfliessendes zueigen, sie sind zerrissen und vollkommen zugleich, in ihrem Furor, ihrer Sehnsucht, ihrer Melancholie.

Was für ein Liederzyklus: „The Colour of Spring“ handelt von Krämerseelen, die sich als Naturromantiker gebärden. „The Gift“ ist inspiriert von dem King Vidor-Film The Crowd, und erzählt vom Verschleudern natürlicher Begabungen. „The Daily Planet“ umreisst das Eindringen der Medien in die Privatsphäre. Mark Hollis war zu der Zeit in Deutschland, als Silke Bischoff beim Gladbecker Geiseldrama auch das Opfer einer zynischen Medienhatz wurde. Die hoffnungslose Lage im Palästina-Konflikt findet genauso ihren Widerhall wie eine Episode aus der Zeit der „Depression“ in den alten USA.

Die Musik des letzten Werkes von Mark Hollis ist der Endpunkt einer langen Reise, ein Gespinst von Klageliedern, die von einer Vergänglichkeit in die nächste stürzen, und dabei kein Verfallsdatum tragen. Eine gute Handvoll Interviews gab der Mann aus Tottenham damals, rund um die Jahreswende 97/98, es waren die letzten seines Lebens, bevor er sich ins Privatleben mit seiner Familie zurückzog. Ich traf ihn im Hamburger Hotel Atlantic. Es war ein herzliches Wiedersehen, sieben Jahre nach unserem Londoner Treffen, nach dem Erscheinen von Laughing Stock. Mark Hollis ist am 25. Februar 2019 gestorben.

Michael: Mark, deine neuen Songs scheinen zu einer anderen Art der Ruhe gefunden zu haben. Weniger Wildheit und Wildnis als auf den beiden Vorgängern, und doch höre ich ich eine enorme innere Spannung heraus.

Mark Hollis: Ich wollte zurück zur einfachsten, grundlegendsten Aufnahmesituation. Ich wollte die Klänge so berühren, dass sie nicht gesäubert oder poliert klingen. Der Sound sollte den Charakter der Instrumente wahren. So nah wie möglich wollten wir herankommen an den realen Klang der Instrumente im Raum.

Michael: Kannst du etwas mehr von diesem Raum erzählen?

Mark Hollis: Der Raum, in dem die Musik entstand, ist diesem hier sehr ähnlich. Es beginnt immer mit dem Raum. Als erstes hörst du auf dem Album den Raumklang in aller Stille. Dieser Sound ist ein bedeutender Teil des Albums und immer wieder hörbar. Jeder Musiker hat eine klar definierte Position. Ich höre mir die Musik am liebsten mit dem Rücken zu den Lautsprechern an. Dann kommt es mir so vor, als wäre ich mitten im Raum. Wenn du intensiv genig lauschst, kannst du die Positionen der Instrumente genau lokalisieren. Du kannst hören, wo das Piano platziert wurde, wo genau Piano und Bass in Schwingung versetzt werden, und wo sich im jeweiligen Moment die Spielhand befindet.

Michael: Wie wurde diese leise Musik von den Mitspielern wahrgenommen, so weit weg vom traditionellen Gestus der Rockmusik?

Mark Hollis: Wir fahren die Instrumente auf eine so niedrige Stufe herunter, dass der Nachhall so bedeutend wird wie das Erklingen der Instrumente. Es ist schon verblüffend, wieviel Raum auf dem Band zu hören wird, wenn man das Volumen so weit zurücknimmt. Für einige Musiker war das eine Überraschung, die waren so sehr an grössere Lautstärke gewohnt, und meinten anfangs, nur laute Töne könnten einen Raum vergrössern. Aber das ist überhaupt nicht der Fall. Wenn du die Ohren auf solch feine Strukturen einstimmst, kann sich ein faktisch kleiner Raum sehr gross anfühlen.

KLEINER AUSFLUG ZUM TONMEISTER NACH LONDON

Ein paar Tage nach der Begegnung mit Mark Hollis sprach ich am Telefon mit Phill Brown, der Mann, der hinter den Reglern Geschichte geschrieben hat, und auch bei den beiden letzten Talk Talk-Alben dabei war, bei monatelangen Sessions, gnadenlosen Löschungen des Materials, auf der erschöpfenden Suche von Mark Hollis und Co. nach der idealen Synthese von freier Improvisation und finaler Gestalt.

Phill Brown: Im Vorfeld hatten wir drei Studios zur Hand, die brauchbar schienen für Marks Vorstellungen für sein Soloalbum. Das eine war das „Air“, das andere „Land‘s Down“. Wir hatten eine hübsche Sammlung von Mikrofonen, das Telefunken-47, das Neumann-48, und viele andere, wir probierten sie alle aus, und hörten, wie sie klangen, wenn eine akustische Gitarre oder Perkussion zu hören waren. Wir entschieden uns für zwei Röhren-Stereomikrofone, zwei Neuman M-49s, sie kamen am ehesten an das heran, was wir wollten. Wenn du bedenkst, dass wir für kein Instrument Equalizer einsetzten, dann liegt es allein an den Mikrofonen, das ehrlichste Bild des Raumes zu vermitteln. Nach einiger Zeit fanden wir das Air-Studio zu lebhaft, „Land‘s Down“ war akustisch zu tot, also wählten wor das dritte Studio. Wir haben keine Klangfilter benutzt und keine Kompression. Das Studio war für einen bestimmten Sound hergerichtet, und das galt für alle Instrumente. In der Abmischung benutzten wir lediglich „spring reverb“ für die Stimme, eine historisch sehr frühe Form eines Hallerzeugers. In den Sechzigern gab es das „EMT-echo-play“, das einen sehr natürlichen Nachhall hatte. Das „spring reverb“ ist, wie gesagt, viel älter, und es bekam den Vorzug. Wir versuchten, eine Aufnahme zu machen, die den Jazzprodukrionen der frühen Fünfziger Jahre nicht unähnlich ist. Damals waren die Musiker sitzend um ein einziges Mikrofon gruppiert, und wer ein Solo zu spielen hatte, musste aufstehen.

FORTSETZUNG IM HOTEL ATLANTIC

Mark Hollis: Was den Sound angeht, dämpften wir das Studio noch, weil es anfangs etwas harsch klang. Die Optik des Raumes war nicht besonders einladend. Oft schalteten wir das Licht runter. Wenn aber die Holzbläser spielten, musste das Licht voll aufgedreht sein, damit die Noten zu lesen waren. Die Musik hatte viel mit Konzentration zu tun, die optischen Reize der Umgebung verschwanden beim Spielen. Ich glaube, die meisten spielten mit geschlossenen Augen.

Michael: Viele traditionelle Rockkritiker sind hier überfordert, die bevorzugte ihre Urstoffe hören wollen und sicher elektrische Gitarren vermissen. Dabei ist diese Musik sehr, sehr intensiv.

Mark Hollis: Ganz sicher. So war es sehr anstrengend, für Mark Feltham die Mundharmonika so zu spielen, dass sie sich in den vorwiegend leisen Gruppensound einfügen konnte. Bei anderen Instrumenten ist das leichter zu erreichen, aber bei der Mundharmonika musst du dich wahnsinnig anstrengen und enorm viel Kraft aufwenden, um einen ruhigen Ton zu produzieren. Ähnlich verhält es sich bei nahezu tonlosen Phrasierungen einiger Gesangspassagen.

Michael: ich glaube, daher rührt auch die seltsame Intensität einer nur an der Oberfläche so ruhigen Musik.

Mark Hollis: Ich wollte drei Areale der Musik einbeziehen, das klassische Feld, den Jazz, und eine Art von Folk. Ich stellte mir ein kleines Kammerensemble vor, oder eine Folkgruppe. Welche dort gebräuchlichen Instrumente könnte ich da hernehmen? Ich wollte, mit Blick auf die Farbenskala, mit etwa fünfzehn, zwanzig Instrumenten arbeiten. Zugleich wollte ich immer nur eine kleine Anzahl von Instrumenten einsetzen. Stets eine sehr begrenzte Gruppe von Tönen, bei Wahrung der Vielfalt. So hast du die Möglichkeit, in diese drei Areale hineinzutreiben, und wieder hinaus. Für einen Augenblick scheinst du dich inmitten eines klassischen Ensembles zu befinden. In der nächsten Minuten bewegst du dich durch eine jazznahe Stimmung. Diese Vorstellungen bestimmen die Auswahl der Musiker, beispielsweise die Holzbläser. Der Klarinettist musste für micn ein Jazzmusiker sein mit einem ausgeprägten Verständnis fürs Klassische, und beim Oboisten war es umgekehrt. Laurence Pendress spielt das Piano und das Harmonium, er hat einen wichtigen Anteil an der Wirkung des Albums, er ist einer der wenigen, die mühelos durch die drei Zonen gleiten können. Seine Art, sich den Klängen zu nähern, war so unglaublich zurückgenommen, du konntest fast nicht den Anschlag hören. Ihn zu finden, war ein Glücksfall, er ist der Musiklehrer meiner Kinder in der Schule.

Michael: Ich finde es faszinierend, wie die Holzbläser an einigen Stellen auftauchen, sich entfalten, und wieder verschwinden. Wie ich las, ist die Musik weitgehend auskomponiert, allein das Trompetensolo auf dem Anti-Heroin-Song „The Watershed“, und der Harmonika-Part auf der „bridge“ von „The Daily Planet“ waren nicht im Vorfeld geschrieben.

Mark Hollis: Du weisst, wie bedeutend für mich die Alben „Sketches of Spain“ und „Porgy and Bess“ von Miles und Gil Evans sind, über zwanzig Jahre hat die Verbindug zu diesen zwei Schallplatten schon gehalten. Ihre besondere Stärke ist die Balance zwischen sehr sorgfältig gestalteten Arrangements, und der sehr offenen, freien Ausführung. Bei „Laughing Stock“ und „Spirit of Eden“ jatten wir eine ähnliche Haltung. Nur dass damals nichts im Vorfeld arrangiert wurde – es war alles frei improvisiert, bis wir in der zweiten Phase die Musik aus stundenlangem Material montierten und destillierten. Für dieses Album ist zwar nahezu alles im Vorhinein notiert worden, aber in der Interpretation wirklich offen.

Michael: Das Lied „A Life (1895-1915) erzählt vom kurzen Dasein eines Menschen, dem erst grosser Fortschrittsglaube begegnet, dann unheilvoller Nationalismus, bis der Erste Weltkrieg sein Leben auslöscht. Und da taucht auf einmal ein ätherischer weiblicher Chor auf.

Mark Hollis: Als ich die Musik für diesen Chor schrieb, wollte ich eine Tradition ländlicher Folklore aufgreifen. Eine elementare Struktur, ein Lied der Leute, und doch nahezu ein Mantra, in der Art, wie sich die Verse im Kreis drehen. Eine Melodie, die durchaus freudvoll vorgetragen werden könnte, wird hier zu einem Chor von Menschen, die an einem Grab stehen, ein leiser, murmelnder Klagegesang.

Michael: Und auch wenn hier viel Geschichte anklingt, die Kompositiomen lassen sich nie als rein „politische“ oder „historische“ Lieder fassen. Keine lineare Story, keine eingängigen Refrains. Es dreht sich stets um die tieferen Schichten von Leiden, von Schmerz. Nur das Wort, das schon im Gesang zerfällt, scheint gültig zu bleiben. Man ahnt den emotionalen Kern, auch wenn die Worte nur bruchstückhaft bewusst werden. Wie etwa auf „Westward Bound“…

Mark Hollis: “Westward Bound“ begann mit der Idee, einen Song in der Tradition von Johnny Cash zu schreiben, aber ihn dann in einer Weise zu realisieren, der für die Denkweise von Country & Western völlig fremdartig ist. Nur von der Basismelodie und der Intrumentierung her könnte er sich in das Genre einfügen. Das Lied ist angesiedelt zur Zeit der amerikanischen Depression. Ein Mann und eine Frau, sie erwartet ein Baby, die wirtschaftliche Lage ist deprimierend. Zwei Dinge gehen gleichzeitig durch seinen Kopf, die Freude über die bevorstehende Geburt, und der extreme ökonomische Druck. Auf das Singen übertragen heisst das: er hat dieses Leid in seinem Kopf, möchte aber auf keinen Fall seine Frau damit belasten, und verstummt innerlich. Der Druck ist aber so gross, dass er über die Lippen kommt. Der Mann versucht, dass die Stimme nur Denken ist, kein Gesang.

Mark Hollis sitzt gerne in einem stillen Raum.

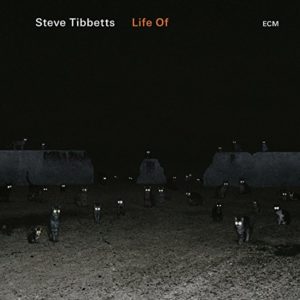

Ich schaue mir das Bild auf dem Cover an.

Mark Hollis: In Sizilien gibt es viele Osterprozessionen. Zu diesem Anlass fertigt man Gebäck an, welches das Lamm Gottes darstellen soll. Der Fotograf hat dieses Bild gemacht, weil die Augen auf diesem Teilchen so vollkommen jenseitig wirken, als stammte das Geschöpf von einem anderen Planeten. Der Glitzerschmuck auf der Stirn erschien mir wie ein Symbol für das Strömen von Ideen.

NACHKLANG 1

Das Strömen von Ideen in kleinen, unendlichen Räumen.

NACHKLANG 2

Das ist das Paradoxe, die Lieder umkreisen Verlöschen, Versagen, Verschwinden, treiben die Töne an den Rändern des Nichts entlang. Und doch ist jeder sich bildende Klang noch Hoffnung, noch Schönheit, noch Bewegung. Als ich immer mehr in den Sog dieser Lieder geriet, fiel mir eim Gedichtband in die Hände, wie ein fernes Echo dieser Lieder, „Dreizehnte Vertikale Poesie“, von Roberto Juarroz. Ein Gedicht darin lautet so: „In jede Lücke ein Bild legen: / ein Flügel, aufgelöst in Licht, / oder eine Stille, umgeben vom einem Blitz. / / Und wenn man bei der letzten Lücke ankommt, / es für alle Fälle leer lassen. / Es könnte das schönste Bild sein.“