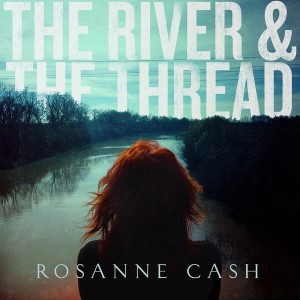

„Even the lightest-hearted of Rosanne Cash’s superb 35-year repertoire often carries with it the weight of history, the struggle for self-discovery and a sense of place. It’s hardly surprising given her station, born to the first family of American music royalty. On The River & The Thread, Cash’s first album of original material in seven years, and the first since brain surgery in 2007, those vibes run deeper than ever, plunging into complicated emotions, impossible situations, piquant insights, fate and history, and the meaning of it all in the land of Dixie.

Playing like a travelogue through time, space and place, The River & The Thread opens – with a yawning, bluesy guitar chord – in the northwestern Alabama burg of Florence. This is “A Feather’s Not A Bird”, and it finds Cash flitting between emotional and geographical landscapes to a sinewy, swampy mix of hot-wired guitars, silky harmonies and a revelatory, ominously impassioned vocal. The setting could be right now, or 100 years either direction. “There’s never any highway when you’re looking for the past,” she declares, part of a kind of cumulative taking stock.“ (Luke Torn, Uncut Magazine)