Tracklist

- Spin Cycle

- Forever and ever endeavour (devour)

- Oops Delores

- Inside Out

- Viola Interlude

- This Precious Time

- Rising Damp

- Rock me Tender

- Good Enough

- Fly-away-home

- Just a minute, not even

- Goodbye Song

on life, music etc beyond mainstream

You are currently browsing the blog archives for the month Juli 2018.

2018 10 Juli

Manafonistas | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | Tags: Aby Vulliamy | 1 Comment

Tracklist

2018 9 Juli

Brian Whistler | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | 2 Comments

Saturday night’s performance of Iranian master singer Mahsa Vahdat with the Norwegian SKRUK choir and Tord Gustavsen (piano/arrangements,) was incredible. One of the more memorable concerts I have attended in recent years … or maybe ever.

The heart of this project is Mahsa Vahdat’s amazing voice, which melismatically keens, swoops and uulates, bringing out all the beauty, longing and nuance of the poetry of Hafiz and Rumi, (sung in Farsi – the choir sings in Norwegian.)

The concert also introduced me to two albums, both of which I purchased on the spot. The album that represents this project is SKRUK & Mahsa Vahdat, i vinens spiel (KKV label) and it’s available on most streaming sites and on CD. Besides Tord Gustavsen, ECM artist, bassist Matts Ellertson (Thomas Strønen, Mathias Eick etc) is on the album. There is also another album (Mahsa Vahdat, Tord Gustavsen and a percussionist,) called Traces of an Old Vineyard, (also KKV) which was also represented that evening when the choir left the stage and the trio performed pieces from that recording.

I bumped into Tord Gustavsen after the show. He told me there will be a new trio album in the fall and extensive touring, even a visit to Northern California. I am happy to hear of a new trio album; for all the other contexts I have heard and seen him in, I still love his trio albums best of all.

SKRUK also performed a cappella, including a mind blowingly beautiful Kyrie written and arranged by Gustavsen (unfortunately not yet recorded.) The choir surrounded the audience for that one. It truly felt like I had been transported to heaven. A transcendent musical evening.

2018 8 Juli

Michael Engelbrecht | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | 4 Comments

Vor vielen Jahren bekam ich das Angebot, vier Stunden am Tag, in einem „independant tea and coffee shop“ in Soho, London, als Servicekraft zu arbeiten, gleichzeitig „alternative coffeehouse music“ aufzulegen (mit zwei Cd-Spielern) – neben einem ordentlichen Salär konnte ich in einer kleinen Wohnung im selben Haus frei wohnen. Der Spass dauerte sechs Wochen und wurde von einem guten Bekannten der BBC vermittelt, in einem Projekt, das Radiomenschen in ungewohnte Settings unterbrachte. Da lernte ich auch die Zubereitung von cremig grünem Matcha Latte mit Eiswürfeln. Ich war einst argentinischem Matetee sehr zugetan, als ich rauschhaft Julio Cortazars Meisterwerk „Rayuela“ durchlebte, doch Mate und Matcha sind zwei verschiedene Kaliber, der kalte Matcha war für mich ein ekliges Gesöff wie selten eins. Soll gut gegen Krebs sein, und ich kenne kluge Leute, die ihn sogar köstlich finden, Martina etwa, wie sie jüngst in ihrer Geschichte zu „Sans Soleil“ kundtat. Allein optisch ist der Iced Matcha-Latte schon eine einzigartige Kreation. Das Matcha-Pulver wird aus den zerstoßenen Teeblättern hergestellt. Der Trinker nimmt also keinen Extrakt zu sich, wie es bei normalem Tee üblich ist, sondern konsumiert das gesamte Blatt. Der Matcha-Tee wird in Japan auch gerne als “grüner Espresso” bezeichnet – der Matcha-Latte ist dann wohl der grüne Latte-Macchiato! Die Zubereitung des Matcha-Latte ist relativ einfach und nicht komplizierter als die Zubereitung eines normalen Latte-Macchiatos. Alles in allem also die perfekte Latte-Alternative im Sommer, wenn man dieses Gesöff halt mag. In dem Laden war es damals das Szene-Getränk no. 1. Die Zubereitung ist einfach, und außer dem Matcha Pulver und Milch sind keine besonders exotischen Zutaten notwendig: 1/2 TL Matcha Pulver, 50 ml heißes Wasser (80°C), 200 ml kalte Milch, 1 Handvoll Eiswürfel. Lassen Sie sich also nicht abschrecken von meinem fast schon körperlichen Ekelgefühl, ich finde ja auch Marzipan und Buttermilch widerlich. Viel interessanter waren aus meiner Sicht die vielen tollen Musikgespräche mit Gästen aus allen Altersgruppen, während meine Musik lief. Jeden Morgen lag auf jedem schwarzlackierten Tisch ein Flyer mit dem „drink of the day“, und den Namen von drei Musikern, die sich zwischen 8 und 12 Uhr munter abwechselten. Diese Blätter habe ich jüngst auf dem Dachboden gefunden, aber sie sind grau und hässlich geworden mit der Zeit. Hier einige der „Blue Morning Music Wonders“, „Trios“ der besonderen Art, Musik, die man, von Ausnahmen abgesehen, tatsächlich eher spätabends, nachts, oder nie zu hören kriegt: Brian Eno / Tuxedomoon / Steve Tibbetts ——- Jon Hassell / Ras Michael / Joni Mitchell ——— John Martyn / Penguin Cafe Orchestra / Bill Connors ——— John Surman / Vaughn Williams / Jacques Brel ——— Nits / Talking Heads / Caetano Veloso ——— Sun Ra / Nick Drake / Cluster ——— eine kleine Auswahl. Es gab in diesen sechs Wochen ausser ethnischer Vielfalt, nahegehenden Begegnungen und einem Hauch von Routine noch eine besondere Sache, die ich nicht unerwähnt lassen möchte. Ben, der Chef des Lades, bat mich, allabendlich eine Runde mit dem Hund zu gehen, ein Golden Retriever namens Mister Phelps. Auf den Strassen von Soho möge ich den Hund zudem stets mit vollem Namen ansprechen, was zu witzigen Situationen führte. Ich verstand mich grossartig mit Mister Phelps, er war offensichtlich ein Fan der Talking Heads, bei Psycho Killer führte er gar ein Duo mit David Byrne auf. Allein, wenn ich seinen Namen rief, schauten die Leute immer wild umher, welchen Gentleman ich da zur Raison rief, und dachten wohl, ich wäre ein weiterer Irrer, der mit Geistern kommuniziert. Der tiefere Witz der Story ist, dass ich ein Jahr später, in der Normandie eine kurze Affäre mit einem britischen Photomodell in den zweitbesten Jahren und einem astreinen Audrey Hepburn-Pony hatte – sie hiess, bingo, Mrs. Phelps, und ich nannte sie auch immer so (was im Bett dann schon mal den Charme einer Rock Hudson-Komödie hatte) – ihr früh verstorbener Mann war der Gründer einer Gruppe, die sich fast in Vergessenheit geratenen Vertretern des „spiritual jazz“ zuwandte, und regelmässig in einem englischen Jazzmagazin publizierte. Mrs. Phelps war vom Jazzvirus ihres Mannes infiziert – und sie hatte einen Riesenfundus an Platten, bei denen der Jazzpianist Stanley Cowell mitwirkte, ihr Lieblingsalbum war „Illusion Suite“.

„Die Sache, die den meisten von uns fehlt, und vor allem auch den Cineasten, das ist die Z-e-i-t. Die Zeit zu arbeiten, und auch nicht zu arbeiten, die Zeit zu reden, zuzuhören und – vor allem – zu schweigen, die Zeit zu filmen und keine Filme zu machen, zu verstehen und nicht zu verstehen, erstaunt zu sein und zu warten auf das Staunen, die Zeit zu leben.“ Dies schrieb Chris Marker in einem Essay zu „Kashima Paradise“, einem Dokumentarfilm, der im Jahr 1974 in Paris lief. Chris Marker hatte sich Zeit genommen, für ausgiebige Reisen, fürs Fotografieren, zum Schreiben. Er setzte verschiedene Mythen über seine Herkunft in die Welt, benutzte einen Künstlernamen und ließ sich nicht gern fotografieren. Anfang der 50er Jahre begann er, Filme zu drehen. „La Jetée“ (1962) ist ein Science-Fiction-Kurzfilm, eine Erzählung, die aus einer Aneinanderreihung von Schwarzweißfotos besteht. Es geht darum, Zugang zu einem zentralen Erinnerungsbild zu finden. Wir befinden uns in einem zerstörten Paris während oder nach dem dritten Weltkrieg. Eine Eschertreppe. „Sans soleil“ oder auch „Sunless“ kam 1983 in die Kinos und wird unter der Rubrik „Essayfilm“ gehandelt. Es ist ein Meisterwerk, ein Meilenstein in der Filmgeschichte. Ich habe „Sans soleil“ erst vor etwa vier Jahren gesehen, da muss der Film im Fernsehen gelaufen sein, ich fand den Film konfus und anstrengend, aber auch anziehend und ich spürte, dass der Film etwas hatte, mit dem ich mich genauer beschäftigen wollte, wenn die Zeit dafür passend war, weil ich den Zugang haben würde, zu dem Themenkomplex Reise, Erinnerung, Gedächtnis, Unterbewusstsein, Geschichte. Normalerweise würde kaum jemand den Text zu einem Film recherchieren und lesen wollen. Bei „Sans soleil“ macht es Sinn, jedenfalls wenn man versuchen möchte, das Gespür für die Magie des Filmes zu verfeinern, das Wiederaufgreifen von Motiven, das Januarlicht auf den Treppen, die Zeremonien, Verführungsrituale, die Poesie und wie Hunde herumtollen am Meer. Ich gehöre zu denen, die es lieben, sich zu verzetteln, cut-ups in Raum und Zeit, und ich saß mit einem kleinen Ordner an Filmbesprechungen zu „Sans Soleil“ und Essays aus Fachbüchern in einem Café-Antiquariat in Budapest, die Nachmittagssonne schien schräg auf die Bücherregale, ich hatte einen iced Matcha-Latte ausgewählt und es war wahrscheinlich der friedlichste Ort, den ich in dieser Stadt finden konnte. Die Offenheit in der Struktur, das Gegeneinanderspiel von Bild, Ton und Text, das Gesagte und das Ungesagte, eine Liste von allem, was das Herz höher schlagen lässt. Bruchstücke eines Spiegels, das Eintauchen in einen kollektiven Traum. Eine Frau gibt wieder, was ihr ein Mann (der Kameramann) schrieb oder erzählte. Der Reichtum an Themen ist enorm, manches wird angerissen, angedeutet, an anderer Stelle wieder aufgenommen oder auch nicht. Der Text ist weitaus eigenwilliger als ein traditioneller Essay. Der Film gibt vor allem Einblicke in die japanische Alltagskultur, kleine Alltagsrituale, das Stehenbleiben vor Ampeln, der 15. Januar als der Tag der zwanzigjährigen Frauen, die mit ihren Winterkimonos durch die Straßen spazieren. „Die Weide betrachtet umgekehrt / das Bild des Reihers“ (Basho). Wie funktioniert das Erinnern? Wie funktioniert das Vergessen? Es gibt das Denkmal eines treuen Hundes, der seinen Herrn jeden Tag am Bahnhof erwartete, auch als dieser gestorben war. Kaum jemand im Westen weiß vom kollektiven Trauma in Okinawa gegen Ende des zweiten Weltkriegs. Chris Marker hat das Thema in seinem Film „Level five“ wieder aufgegriffen und dabei die Witwe des Programmierers eines Computerspiels in den Mittelpunkt gestellt, in ihrem Versuch, im Computerspiel den Verlauf der historischen Geschehnisse zu verändern. „Sans soleil“ ist ein Palimpsest, eine Partitur, die Einblendungen diverser Dokumentarfilme anderer Filmemacher enthält. Bilder aus Afrika, aus Island, aus Guinea-Bissau. Auch mal: minutenlanges Schweigen. Das Herzzerreißende der Dinge. Flaschen, die aus dem Fenster geworfen wurden. Es gibt die „Zone“, ein Begriff, der allen vertraut ist, die Tarkowskijs „Stalker“ gesehen haben, und der hier, bei Chris Marker, für die eigene Erinnerung steht: bearbeitetes Material, speicherungsfähig. Das Digitale, seine Möglichkeiten, seine Zerstörungskraft. „Sans soleil“, das ist, so heißt es im Text, eine Materialsammlung für einen Film, der nie gedreht werden soll. Und sind es nicht die Widersprüche in einem Kunstwerk, die wir suchen, die Leerstellen, die Risse, durch die wir die Kraft des Lichts umso intensiver fühlen, weil wir sie nur ahnen? Es gibt eine längere Passage über den einzigen Film, der, so heißt es, das wahnsinnige Gedächtnis auszudrücken vermag, Hitchcocks „Vertigo“. Die Suche nach den Schauplätzen in San Francisco. Alles war da. Die Brücke, das Auge des Pferdes, die Bucht. Der Briefschreiber (Chris Marker oder der Kameramann) hat „Vertigo“ neunzehn Mal angeschaut. So weit würde ich nicht gehen. Ich könnte mir eher vorstellen, „Sans Soleil“ neunzehn Mal anzusehen. Der Film ist in seiner Gesamtstruktur so wenig greifbar wie die Magie eines vielschichtigen Gedichtes, er entsteht in jedem Betrachter auf andere Art. „Sans soleil“, das ist auch der Versuch, sich an einen Moment des Glücks zu erinnern. Der Film beginnt mit einem schwarzen Startband, ein Moment des vollkommenen Glücks. Die Schnitttechnik zeigt erst am Ende, wie gefährdet dieses Glück bereits zu Beginn des Filmes war. „Sans soleil“ ist der Versuch, einen Trost zu schaffen, für etwas, wofür es keinen Trost geben kann.

2018 6 Juli

Michael Engelbrecht | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | Tags: Aby Vulliamy | 4 Comments

Multi-instrumentalist, singer, composer, lover of free improvisation, and music therapist Aby Vulliamy takes a long look back to first musical revelations and „non-musical“ sounds from an old clock in the hallway to birdsong. She gives insights in her love and learning of instruments, and how someone encouraged her to trust her voice to sing. I really didn‘t know much about her musical life when I first contacted her. Simply being fascinated with her viola and rare vocal contributions on the last two installments of Bill Wells‘ fabulous National Jazz Trio of Scotland (Bill has a knack for special voices!), and reading about her therapeutic activities, this was enough for me: a starting point.

The diversity of her musical activities goes way beyond the viola and vocal moments on Bill‘s albums, but sometimes a small snippet, the bending of a note, are enough for stopping you in the tracks. I would be very surprised if she didn‘t have David Darling‘s „Cello“ or the early albums of The Penguin Cafe Orchestra in her record collection. Also, I do think (after our first „conversation“), she must certainly be in love with Kate Bush’s song „Mrs. Bartolozzi“ – and, talking about ancient, worn-out instruments, she followed the link leading to my recent interview with Steve Tibbetts – and „Life Of“ will soon have another listener in Glasgow.

Aby Vulliamy also thinks back of growing up in Hull. A town that I only know from the history of lucid dreaming. Psychologist Keith Hearne made his famous discovery concerning ocular-signaling from the lucid dream state on the morning of 12th April 1975, at Hull University’s sleep-laboratory. He communicated the data, and other examples, to Professor Allan Rechtschaffen of Chicago University. Much later, Stephen LaBerge, at Stanford, produced similar work. In following conversations I will (and do write this with a big smile) try to raise her interest in the subject. By the way, when these conversations will come to an end, her debut album will have been released, in October, on Karaoke Kalk.

I remember hearing Keith Jarrett’s Koln concert for the first time maybe in my late teens, and just being blown away by the fluency and energy of his piano improvisation. Someone made me a cassette tape of it, and I kept it for about 15 years until my tape player broke. It’s the only music I could ever listen to whilst writing essays or reports – somehow although I loved it, it didn’t distract me like all other music did, it helped give me momentum and energy and focus. I remember listening to a Charles Ives piece years later and finding some of it familiar, and realising that Jarrett references it in his Koln concert, and I’m sure there are many other references in there too.

Abdullah Ibrahim’s Water from an Ancient Well has accompanied me for a long time too. My dad once said the trombone sounds like a bull elephant and it often makes me tearful when I hear it. Also Ibrahim’s duo as Dollar Brand with Johnny Dyani (Good News From Africa) will stay with me throughout my life, I’ve no doubt; it’s their liberated vocals and intuitive connection with each other, I love it.

I’m not sure there is such a thing as a non-musical sound experience? Everything can be viewed through a ‘musical lense’, it’s just whether it’s received as such by the listener. People say to me ‘I’ve not got a musical bone in my body’ but we’ve all got a pulse, we’ve got a unique tone of voice and particular pitch range, we have a natural walking pace etc. All communication is based on the elements of music; rhythm, tempo, timbre, melody, pitch contour etc. We are all musical beings.

Aidan Moffat and Bill Wells used the clicking of a car indicator as the opening sound which dictates the rhythm and pace of the first track on their brilliant 2nd album, The Most Important Place in the World. We had a beautiful old grandfather clock (since stolen) in our hallway when I was growing up, and it’s background ticking and hourly chime structured my childhood, making me feel safe. I would always be subdividing the rhythms in my head, or practicing 3 beats over 2 etc.

There must be millions of examples of ‘non-musical’ sounds being incorporated into music, or inspiring composition. Washing machines are musical; I often find myself humming harmonies or singing along to the drone of the washing machine. I can often hear different frequencies the more I listen to simple drones. Birdsong is of course music, it has plenty melody and repetitive rhythmic patterns, although birds don’t get any publishing rights. I love Messiaen’s crazy birdsong inspired organ pieces, and of course Vaughan Williams’s Lark Ascending. Melodies from birdsong feature in loads of folk music.

I grew up in Hull. Its a very special place, home to some beautiful people. But it gets so much bad press and has some terrible statistics in terms of life expectancy, teen pregnancy, addiction problems, poverty etc. It’s the end of the line, and I think it’s quite hard to get bands to include Hull on their tour schedule, although Paul Jackson of the very special Adelphi Club has single-handedly changed the lives of many local music-lovers and musicians by persuading a fabulous array of touring bands to make the detour to Hull.

Music was escapism for me. I grew up in a very busy household with my 3 brothers and 1 sister and many visitors. I was shy and quiet and not assertive, but when I was practicing my Khachaturian on the piano I was like a different person! I loved the Russian composers, they’re wild and intense. My piano teacher used to enter me into the competitive music festival, at the magnificent and overbearing Hull City Halls, which seems like a terrible idea (music as competition?!?) but in fact I think it helped me a great deal with performance anxiety – I mean, what’s the worst that can happen? Now, music is a social thing for me and it has been the way I’ve made new friends in each new city I’ve moved to. I need to play – after water, food, shelter, love – I’d soon go mad if I didn’t play music.

My mum and dad are music lovers but not musicians themselves. All 5 of us siblings played instruments at various points; 2 brothers played double bass, one played cello, my sister played clarinet, and we had the piano too. What a fabulous ensemble that would have been! But we never played altogether, sadly. My sister and I did some duets far too occasionally, which was always a treat to me.

My dad’s dad was a brilliant pianist and I inherited his beautiful faded black baby grand piano when he died. I feel sad I never became accomplished and confident enough to play the wild Rachmaninov duets that he wishfully shoved in front of me when I visited him.

My mum, despite having 4 other kids and a household to run and studying for a degree etc etc, would sometimes spend her precious time sitting beside me whilst I practiced the piano, coz she knew that it helped me stay focused and motivated, so she did it despite all the other demands on her attention. A gentle, quiet but incredibly powerful and generous gift.

Piano is really my main instrument. All of the songs on my upcoming album were written on the piano, although there are several short viola ‘interludes’ on there too. I had my first piano lessons aged 4, with a music student we referred to as ‘Julie Fingers’, who charged 50p per lesson.

I started on the violin when I was 7, and was given free lessons at school, on a borrowed instrument. I soon switched to the viola. It suits me so much better; it’s deeper, more mellow and rich to my ears. The violin and viola sit so close to the player’s ear, and can sound so jarringly tinny and reedy there; too many high frequencies for my sensitive ears. The viola suits my personality much better than the violin. In orchestral music it’s often hard to discern the viola, you only notice us when we screw up. But we have a really important role to play, supportive and containing; the fabulous Swiss band I play with, Orchestre Tout Puissant Marcel Duchamp XXL recently played a gig without me, and the band leader said it felt out of tune without the viola! Its often the glue that holds parts together, quietly but enrichingly.

My parents bought me my viola when I was about 10, and my mum kept apologising, fearful that I would experience it as a pressure and expectation. I love that viola so much! I still use the same one, and though I’m often surrounded by musicians who’s instruments cost 10’s of £1000’s more than mine, I feel safe and solid with my trusty old viola. It’s like an extension of my body- it’s getting a bit old and battered but it’s strong and resilient and full of instinctive memories.

I think at first I just went along with the music lessons I was offered, but didn’t initially feel very moved by the music, strangely. People were encouraging, and I knew I was lucky to get free lessons at school, so I kept going with it. I’m gutted that nearly all music services in British schools have to be paid for now, so that learning an instrument is only for children with families who have spare money. I believe that the opportunity to learn an instrument as a child is one of the most powerful and influential experiences available; it could be key to solving some of the major societal problems we face; intergenerational poverty, unemployment, demoralisation, depression and addiction. The Big Noise project which is now well-established in some of the most deprived communities of Scotland (based on the Venezualan El Systema model) has far-reaching goals and some amazing statistics and research showing how the discipline, team-work, mutual responsibility, co-operation, shared purpose of music-making have a huge influence on positive development in terms of self-worth, self-awareness and social conscience. At the same time, making music is a form of self-expression and communication that can process feelings that are otherwise too strong and disturbing, and can provide an intimacy that it is hard for some people to access using just words. Learning music enhances so many crucial skills; academic (particularly maths) and life skills such as self-esteem and communication skills, it’s crazy to deny children this. For the tricky teenagers, that I work with as a Music Therapist, music can be a form of expression far more powerful than words – a place where they can feel heard and understood and accepted and valued for who they are.

I started with classical music on both piano and viola. Although I know how lucky I am for the opportunity to learn classically, I sometimes regretted the limitations of a purely classical training, when, aged 17 or so, I began to make music with my friends who had taught themselves to play guitar, bass, drums, and I lacked their confident spontaneity, intuition and creativity. It took time to gain confidence to stop relying on the safety net of music notation and theory, and to just listen and trust my instincts in response. Now I’m very grateful to have both, the theory, reasonable technical knowledge, and instinct/sponteneity.

I think I was 13 when I joined the City of Hull Youth Symphony Orchestra. I remember sitting at the back of the viola section, going through the motions and not feeling very connected to the parts I was playing, when suddenly the 100-piece choir began to sing behind me. My hair stood on end, I felt the force of their voices, my whole body vibrating, the feeling of being part of something immensely powerful. I think this was the first time I was wholly physically and emotionally moved (blown away) by music. I wish I could remember which piece we were playing – I’ve got a terrible memory! I know Verdi’s Requiem has given me the same overwhelming feeling since.

My dad got into jazz when I was a young teen, so having provided the obvious musical foundations of a 70’s child (Bob Dylan, the Incredible String Band, Bonzo Dog Dooda Band, Van Morrison, Pink Floyd, Dire Straits (almost exclusively male line-ups I now realise) he then began playing Abdullah Ibraham and Keith Jarrett as previously mentioned, Brotherhood of Breath, Dudu Pakwana, John Surman, Annie Whitehead, District Six, Jessica Williams, Colloseum (Tanglewood 64 – I played that when I was in labour with my first daughter. I love men singing, and in this case they’re using their voices as instruments, just ‘bah’ing the melody – it’s ace) etc etc. Brilliant stuff.

I also loved Funk/Northern Soul in my later teens. I joined my first band at 18, playing folky-style viola over guitar-based songs sung and played by my friend Shelley’s dad and his pal. Also a funk ensemble with me and my teenage friends as the rhythm section (I played ‘the Beast’ a ridiculously heavy old electric organ) and my friend’s Social Worker parents as the horn front line. We initially called ourselves ‚The Funkateers’, but decided to add an extra prefix every time we played a gig; we got as far as ‘the Almighty Allstar Funkateers coz gigs were hard to find in Hull and it was time for the younger generation to buzz off to university. And now I’ve come full circle, playing in another (much better) band making tongue-in-cheek claims of superpowers since the ‘Tout Puissant’ of Orchestre Tout Puissant Marcel Duchamp translates as Almighty (All Powerful). It is a very powerful band, the music moves people psychologically and physically, but the power to connect and move is in it’s collectivism and shared emotion, not a reference to a higher being.

The violinists / violists that influenced me are perhaps obvious; my dad subtly introduced me to Stefan Grapelli and although I loved listening to him, it never occurred to me that if I practiced hard enough I should eventually be able to play over changes fluently (Grapelli-style was unachievable but I could definitely improve my fluency). I wish I’d started practicing that earlier, because I’m still not fluent and confident over changes, and there’s no excuse really. My dad also pointed me towards Billy Bang, the ganster-turned-jazz violinist, who’s self-taught style of jazz improvisation was absolutely liberating and unique. I don’t understand why it’s still so unusual to include improvising strings in jazz front lines, they can add such different textures and sounds to the same old wall of saxophones that so many band leaders opt for. Saxophones are beautiful, but why not add something a bit different?!

John Cale (and Velvet Underground) and Laurie Anderson were a revelation and stopped me from wishing I’d learnt a funkier instrument than the viola – their music was immediately accessible for me, and although massively inspired and unique, didn’t feel technically out of my reach. More recently the free-improvising violist Mark Feldman is an obvious person to pick out, and my good friend and improvising mentor, Seth Bennett’s double bass playing is a massive source of inspiration.

I love free improvisation. I know some people find it too disturbing and un-nerving, and I was the same at first (I thought of it as musical masturbation – a self-indulgent exposure in front of an audience), but now it’s free improvisation that makes me feel most alive, to listen to and to perform. The spontaneity, fluidity, the emotional roller-coaster of intensity and dynamics (volume, speed, texture) makes for breath-taking unpredictability, moving through tension and resolution (or non-resolution!), tenderness and aggression, beauty and ‘ugliness’- it’s absolutely liberating. Stephen Nachmaninov writes really beautifully about free improvisation in his book Free Play. Good free improvisation is the ultimate music for me, though I love a lot of differet genres and I fully understand that it takes time to learn how to access and enjoy free improvisation.

In relation to some of the free improvisation I love, the piano-based songs on my upcoming album are very conventional!

When I moved to Glasgow, Scotland, in 2004 it was amazing how quickly people began inviting me to play. I knew only my partner George Murray (trombonist) when I moved up there, but Daniel Padden and Peter Nicholson (The One Ensemble), Chris Hladowski (Scatter, Nalle, The Family Elan), Hanna Tuulikki (Nalle), Bill Wells (NJTOS) and Stevie Jones (Sound of Yell) welcomed me with huge generosity and facilitated many brilliant learning opportunities for me. It’s such fertile and open-minded creativity that thrives up there – people inspire and nurture each others’ musicality with such generosity. There is such potent possibility to jump between genres (and therefore to stretch yourself and learn more). I wonder if it was partly because as a viola player I inherently offer something slightly different to the proliferation of traditional/folk violinists in Scotland. I played in indie, pop, jazz, folk, free-improvisation ensembles, and I did music for theatre/dance, performance art etc and I learnt tonnes.

In Glasgow I also began singing, having always been far too self-conscious to open my mouth- I was too shy and easily embarrassed. It was Hanna Tuulikki who cajoled me into singing with her trio Nalle with Chris Hladowski in 2005/6. I was terrified at first but she insisted and I’m so glad she did. She’d kneel on the floor with me, our thighs touching, sometimes using walkie-talkies to distort the sound, often letting her voice slide fractionally below or above my pitch to create oscillations between us that disorientated and connected us at the same time. It was precarious and exciting.

Not long after that, with his National Jazz Trio of Scotland, Bill Wells began rearranging traditional jazz and folk songs and writing original songs, often leaving the voice brutally exposed, and often at the very bottom of my vocal range, where it’s hard to get a sound out at all, let alone to control the sound of my voice. These were utterly terrifying gigs where my knees shook as much as my voice wobbled. Often the lyrics were devastating and I feared it (and I, as a nervous wreck) would be just too much for the audience to cope with; too raw and fragile and exposed. I’ve learnt that some material is supposed to feel precarious, it wouldn’t work if I could sing it confidently, and audiences generally cope!

I’m well aware of how extremely lucky I am, to have had opportunities to learn several instruments (including lessons on piano, viola and flute), and to have met so many beautiful generous talented musicians who’ve shared musical space and skills and opportunities with me, stretching me and inspiring me to learn more, take more risks, experiment more. For a long time I thought I couldn’t self-generate music; that I was dependent on other musicians to initiate and give me something to respond to and that my main skill was my ability absorb whatever was thrown at me, and come up with creative ideas in response. It took me by surprise when my piano-based songs emerged, and although I’m really proud of finally producing my own material I’m also keen to convey that my new album is not the whole of me, and there is lots more very different stuff to come in the not-too-distant future.

2018 6 Juli

Gregor Mundt | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | 1 Comment

Wenn des Tages Last noch drückt, die Arbeit einfach zu viel war, dann suche ich gerne noch vor dem Zu-Bett-Gehen meinen Plattenschrank auf, und spiele “Ziehe mit geschlossenen Augen eine Platte“. Meist bringt dieses Spiel Überraschungen hervor, ich entdecke dann Platten, an die ich schon Jahre nicht mehr gedacht habe. So auch dieses Mal:

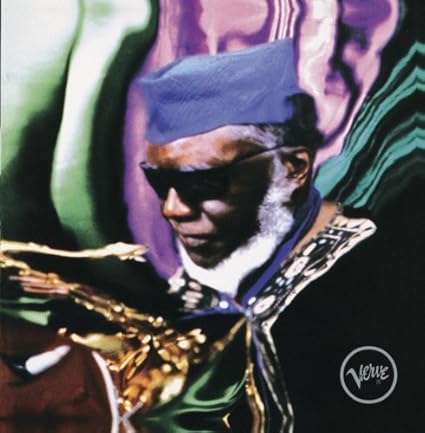

Die Wahl fällt auf das von Bill Laswell produzierte Pharoah-Sanders-Album „Message from home“, mit dabei Michael White, Bernie Worrell, Charnett Moffett, Hamid Drake und Aiyb Dieng. Koraspieler Foday Musa Suso ergänzt die Truppe, wir kennen ihn aus der Zusammenarbeit mit Jack DeJohnette, dem Kronos Quartett, Herbie Hancock, Philip Glass. Zusätzlich arbeitet Sanders auf dieser Platte mit der Unterstützung einiger Vocalisten. „Message from home“ erschien im Februar 1996. Drei Jahre später überraschte uns Pharoah Sanders mit der Album “Save The Children“. Aber auch „Message from home“ ist ein wunderbares Album, ich höre den Titelsong “Our Roots (Began in Africa)“ und bin begeistert, die Platte muss bald einmal mehr in Gänze gehört werden.

Mit dem zweiten Zufallstreffer erwische ich eine richtige Sommerplatte: Philip Catherine “Summer Night“. Diese Scheibe erreichte 2002 die Läden. Der heute 76jährige Gitarrist spielt hier mit Philippe Aerts (b), Joost van Schaik (dr) und Bert Joris (tp). Natürlich lege ich die Philip-Catherine-Komposition “Janet“ auf, bin allerdings etwas enttäuscht, vielleicht habe ich zu sehr die Janet-Version von der Platte im Ohr, die für mich immer noch eine herausragende Veröffentlichung Catherines darstellt: “End Of August“, aufgenommen mit Nicolas Fiszman und Trilok Gurtu. Die für mich beste Schallplattte des Gitarristen ist allerdings immer noch zweifellos “End Of August“ (1974). Remember? Das grandiose Eröffnungsstück “Nairam“, aus dem Robert Wyatt dann “Maryan“ zauberte? Nein? Dann unbedingt noch heute anhören: Robert Wyatt “Maryan“ aus dem Album „Shleep“, das war 1997 – auch schon wieder 21 Jahre her.

2018 5 Juli

Manafonistas | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | 3 Comments

„Frank O’Hara’s poems are exuberant, enthusiastic lists of experiences, feelings, objects and people, with subjects as simple as picking up a new watchband or reading a movie magazine. Often addressed to friends, O’Hara’s poems speak to the reader as an intimate, dropping names and places the way you do with someone you’ve known forever. These poems, dashed off during free moments on scrap paper, typed on store display typewriters, or improvised in personal letters, usually ended up stuffed away in a drawer or even lost in sofa cushions. O’Hara’s books were often composed of whatever he could scrape together digging through his apartment. But their deliriously excited voice captures a poet in love with life, with things, and most of all with people, and their warmth and personality have ensured that, even if he dismissed or forgot his poems, no one who reads them ever will.“

Mit diesem Lied auf den Lippen kam zwischen 1968 und 2001 im amerikanischen Fernsehen Mister Rogers von der Arbeit nach Hause (wir erfahren nie, welchen Job er hatte, aber seinem Aufzug nach wird es wohl ein white-collar job gewesen sein), hängte sein Jackett in den Schrank, zog einen farbigen Freizeitsweater über und nahm Platz, um die Business-Schuhe gegen bequeme Sportschuhe zu wechseln. Diese Geste des Schuhwechsels ist so typisch und so bekannt, dass sowohl das Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh ihn so in der Originaldekoration zeigt …

… wie auch die Mister-Rogers-Statue, die in Pittsburgh vom südlichen Ufer des Allegheny Rivers auf den Point Park blickt, dort, wo der Allegheny und der Monongahela zusammenfließen und den Ohio River bilden:

Won’t you be my Neighbor? ist auch der Titel eines Dokumentarfilms, der zur Zeit aus Anlass des 90. Geburtstages von Mr. Rogers durch die amerikanischen Kinos läuft. Im Normalfall reicht bereits die Erwähnung des Titels oder des Namens, um Amerikaner, soweit sie mit dieser seiner Show

aufgewachsen sind, zu Tränen zu rühren. Und das ist nicht übertrieben.

Fred McFeely Rogers (1928-2003), studierter Komponist, Pianist und geweihter presbyterianischer Priester (der allerdings nie eine Messe las), fand das, was das amerikanische kommerzielle Fernsehen Vorschulkindern vorsetzte, einfach schrecklich. In den frühen 1960er Jahren entwickelte er deshalb eine 15-minütige Kindersendung namens Misterogers, die eine Zeitlang im kanadischen CBC zu sehen war, dann aber eingestellt wurde. Er setzte seine Arbeit fort in seinem Geburtsort Pittsburgh beim Public-TV-Sender WQED. In einfachster Kulisse, mit Handpuppen und einer kleinen Schar ständiger Darsteller, entstand so Mister Rogers‘ Neighborhood. Schon nach kurzer Zeit übernahmen alle Public-TV-Sender der USA die Show in ihr Programm, wo sie dann von 1968 bis 2001 blieb.

Fred Rogers setzte dabei bewusst auf einen Gegenpol zur Sesame Street, die in schneller Schnitt- und Wiederholungsfrequenz das von Kindern heißgeliebte Werbefernsehen kopierte — mit Erfolg, wie man weiß. Rogers war der Meinung, man müsse, um einen Draht zu Kindern zu entwickeln, keine albernen Hüte aufsetzen, nicht betont „kindlich“ reden, nicht permanent schreien oder Witze reißen und auch keine Supergestalt sein. Kennzeichen seiner Show waren relative Gemächlichkeit, Ruhe, unbedingte Aufrichtigkeit, eine Reihe von Ritualen (wie dem eingangs geschilderten), vor allem aber die völlige Freiheit von Werbung und Product Placement.

Mister Rogers verstand es stets, eine gewisse Distanz zu halten: er zog zwar Freizeitkleidung an, aber die Krawatte blieb. Nie wurde er „Uncle Fred“ oder etwas dergleichen, er blieb immer „Mister Rogers“ — im deutschen Fernsehen würde das bedeuten: Er ließ sich siezen. Zwischen der „realen“ Kulissenwelt und der Welt der Puppen verkehrte ein Straßenbahnwagen. Dort traf man dann auf Gestalten wie King Friday XIII und seine Frau, Daniel Tiger oder X the Owl — zehn Charaktere insgesamt sprach Rogers selbst. Mit ihnen konnte er Emotionen aufbauen. Dazwischen gab es kurze Sach-Einspieler über etwa die Herstellung von Himbeereis, oder wie man einen Kran aufbaut, wo Zeitungen herkommen, und so weiter. Im Normalfall wurde die Sendung relativ kurz vor der Ausstrahlung produziert, so dass aktuelle Vorkommnisse einbezogen werden konnten.

Man muss es sehen und hören, wie dieser Mann mit Kindern sprach, mit ihnen umging, ihnen Dinge erklärte, wie er sie ernst nahm, ohne sie zu überfordern. Man muss es sehen (und die Dokumentation zeigt es), wie er — zum Beispiel — erklärt, was der Begriff assassination meint (das Attentat auf Robert Kennedy war gerade passiert und der Begriff ging durch alle Medien), wie er (live im Studio!) vor Kindern auf die Challenger-Katastrophe reagiert oder was 9/11 zu bedeuten hatte. Wer im deutschen Kinderfernsehen hätte das hinbekommen? Ich weiß keinen.

Man muss sich klarmachen, dass noch in den Spätsechzigern manche Hotelbesitzer ihren Swimmingpool desinfizierten, wenn Schwarze darin gebadet hatten. Erst dann kann man verstehen, welchen explosiven Hintergrund eine scheinbar ganz harmlose Szene wie diese hatte:

Der Polizistendarsteller übrigens hatte irgendwann sein reales Coming-Out. Das führte zur Scheidung seiner Ehe, was natürlich Futter für die Klatschpresse war. Mister Rogers konnte auch das in seiner Sendung kindgerecht auffangen, und der Schauspieler blieb im Team.

Und es gibt jenen legendären Auftritt Rogers‘ vor dem United States Subcommittee on Communications, das 1969 über die Vergabe von 20 Millionen Dollar an das öffentliche Fernsehsystem PBS zu entscheiden hatte. Nachdem etliche Fachleute ihren Standpunkt dargelegt hatten und das Komitee nicht zu überzeugen vermochten, rezitierte Fred Rogers schlicht einen Text aus seiner Sendung — eigentlich einen Liedtext, den er aber sprach. Was den bis dahin äußerst widerständigen Chairman schließlich zu der Bemerkung brachte: „I think it’s wonderful. Looks like you just earned the $20 million.“ — So zu sehen in der Doku.

Mister Rogers‘ Neighborhood ist in Deutschland völlig unbekannt. Auch mir als Mediensoziologe war die Sendung nie begegnet. Da sie mit der Person Fred Rogers stand und fiel, wäre es wahrscheinlich unmöglich gewesen, sie in einer sinnvollen Weise einzudeutschen (wie es mit der Sesamstraße ja durchaus gelungen ist). Ich wüsste auch keine Person, die Rogers‘ Stelle hätte einnehmen können — am ehesten vielleicht noch Siebenstein, aber auch das war eigentlich etwas anderes. Das Team der Sendung mit der Maus allerdings (die wiederum hier kein Mensch kennt) hat Mister Rogers mit Sicherheit sehr genau studiert, auch wenn atmosphärisch etwas anderes dabei herausgekommen ist.

Fred Rogers starb 2003 an Magenkrebs. Noch während der Trauerfeier protestierten auf der Straße religiöse Betonköpfe gegen sein teuflisches Wirken.

Ja, ich wäre gern sein Nachbar gewesen. Sollte es die Doku wundersamerweise einmal nach Deutschland schaffen: Anschauen lohnt sich. Bitte dann vorsichtshalber ein Paket Taschentücher nicht vergessen.

2018 3 Juli

Lajla Nizinski | Filed under: Blog | RSS 2.0 | TB | Tags: Buchtipps | 9 Comments

Wir müssen ja Karl Marx nicht wörtlich folgen und den Fisch selber fangen. Aber ihn dann zu Mittag selbst zuzubereiten, liegt sicher in der gemeinten Denkrichtung.

SEELACHS IM SENFMANTEL

4 Seelachsfilets

8 Eier

8 EL Senf (ich nehme den von Uwe mitgebrachten aus Schwerte)

1 Teelöffel Honig

1 Prise Salz und Pfeffer

Etwas Mehl und Öl zum Braten

(FÜR 4 PERSONEN)

Und dann empfiehlt Herr Marx, nach dem Essen zu kritisieren.

Ich habe für Euch gelesen:

Jaron Lanier: Zehn Gründe, warum du deine Social Media Accounts sofort löschen musst

Ich habe die Bücher von Lanier gerne gelesen. Er war von Anfang an dabei, war Gründer und Insider im Silicon Valley. Er ist Computerwissenschaftler und – bitte kritisch beachten – arbeitet für Microsoft. In seinem neuen Buch geht es um Datenmissbrauch und wie wir mit Social Media unser Verhalten modifizieren.

Ich zitiere:

In sozialen Medien ist die Manipulation sozialer Gefühle die einfachste Methode, um Bestrafung und Belohnung herbeizuführen (S.27…)

BUMMER (= Behaviors of Users Modified, and Made into an Empire for Rent) in etwa: Verhaltensweisen von Nutzern, die verändert und zu einem neuen Imperium gemacht wurden, das jedermann mieten kann. (S.43 …) Lanier unterteilt in 6 Komponenten:

–

Die Arschloch Herrschaft

– Totale Úberwachung

– Aufgezwungene Inhalte

– Verhaltensmodifikation

– Ein perverses Geschäftsmodell

– Fake People

Dazu ein Beispiel von Lanier selbst auf S.64:

Für eine Weile war ich Top Blogger der ‚Huffington Post‘, immer auf der Startseite. Aber dann stellte ich fest, dass ich wieder in die altbekannten Muster verfiel, wann immer ich die Kommentare las. Ich schaffte es nicht, sie einfach zu ignorieren. Bei solchen Gelegenheiten fühlte ich eine merkwürdige, verhaltene Wut in mir aufsteigen, manchmal auch einen absurden, glūhenden Stolz, wenn es den Leuten gefiel, was ich geschrieben hatte -selbst wenn das, was sie schrieben, eher verdeutlichte, dass sie sich nicht ernsthaft mit meinem Text beschäftigt hatten. Die Autoren solcher Kommentare suchten hauptsächlich Aufmerksamkeit für sich selbst …

S.77 Was wir brauchen, ist irgendetwas, das jenseits der sozialen Angeberei real ist. … Falls du auf Online-Plattformen aktiv bist und dabei etwas Unerfreuliches in dir selbst bemerkst – eine Unsicherheit, ein geringes Selbstwertgefühl, den Drang, jemanden zu attackieren: dann verschwinde von dieser Plattform.

S.94 Postings von Frauen werden häufig auf groteske Weise aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen, um sie zu demütigen, bloß zu stellen oder zu belästigen.

„Social Media tötet dein Mitgefühl “ S.107 …) Du kannst jdn. nicht verstehen, wenn du nicht zumindest ein bisschen was darüber weisst, was er erlebt hat.

S.124 BUMMER drängt mich in die Position eines Untergebenen. Schon seine Struktur ist eine Demütigung …

S.152 Ich werde also erst dann ein Nutzerkonto bei Facebook, Google oder Twitter anlegen, wenn ich dafür bezahlen darf -und wenn ich das eindeutige Recht an meinen eigenen Daten habe und den Preis für Sie SELBST FESTSETZEN kann …

Und zum Schluss die Frage an Karl Marx: Wann sollen wir Musik hören?

Ich höre seit zwei Tagen immer Ray Davies: Our Country, besonders The Getaway.

Il nome di Jah Wobble presso il grande piccolo pubblico di appassionati di musica è principalmente noto per il suo ruolo centrale nel sound Public Image Ltd., ma inquadrare questo musicista solo all’interno di questo contesto è sicuramente riduttivo. Wobble è infatti un musicista completo e un artista a 360° gradi, un compositore moderno e contemporaneo tout-court: il confronto con musicisti come Holger Czukay e Jaki Liebezeit, lo stesso Brian Eno ha sicuramente senso e ci fornisce un ritratto completo di questo musicista che ha una produzione discografica eterogenea e prolifica allo stesso tempo.

„Dream World“ è stato registrato da John direttamente nel suo studio con la collaborazione dell’amico George King („Havana“, „Dream World“ e „L’autoroute sans fine“), sarà pubblicato sulla sua stessa label senza nessuna particolare promozione. Ascrivibile direttamente sotto la definizione di genere „Jah Wobble“, „Dream World“ è un trip di musica trance acida e che ci cala in una dimensione surreale: „A Chunk Of Funk“ sono sette minuti di groove funky e musica elettronica con sonorità prossime agli Yellow Magic Orchestra; „Havana“ è un tema Isaac Hayes rimescolato dentro uno shaker di musica caraibica; „Cuban“ un jazz afro-caraibico che ruota su un veccho giradischi che fluttua a mezz’aria nel vuoto; „Dream World“ una composizione ambient minimalista; „Strange Land“ praticamente dieci minuti di dub fantasma e ossessivo con sonorità aliene e ipnotiche; „Sleeping Hill“ ha un sound quasi glitch e dove domina imperioso il basso causando stati di paranoia e giramenti di testa; con „On Steriods“ siamo proiettati direttamente in un mondo alternativo settato dentro il videogioco „Space Invaders“; „L’autoroute sans fine“ rievoca una certa elettronica pop tipo Kraftwerk, mentre „Spirits By The Thames“ è un tema cinematico remixato in chiave elettronica e dubstep e che sembra quasi un pezzo Wall Of Voodoo suonato da Black Moth Super Rainbow.

Il legame con la scena punk ancora qui si conferma slegato da ogni estetica del periodo: Jah Wobble è inglese di Stepney nell’East End londinese e nel 1977 aveva 19 anni, come pensare che una figura come lui avrebbe potuto restare indifferente da una fase storica e così determinante per la controcultura del periodo. A differenza di molti tuttavia non si è fermato lì e ha continuato a ampliare i suoi orizzonti culturali e ha creato un proprio mondo: il risultato è una visione più ampia e che continua ad allargarsi sempre di più disco dopo disco fino ad inglobarci tutti dentro un grosso mondo dalla forma e i connotati di uno stroboscopio.

(From Debaser.it)