Perhaps it’s not surprising that the Lijadu Sisters have spent the last 30 years languishing in obscurity. Life as a female artist in the 1970s was no barrel of laughs, wherever you hailed from. It was the era of an all-female rock band called Fanny and Gilbert O’Sullivan’s 1974 hit single A Woman’s Place, which, he reckoned, was in the home. Even at the height of punk, with Patti Smith supposedly overturning outmoded ideas of women in rock, it was somehow deemed acceptable to advertise a new single by Blondie with a picture of Debbie Harry and the tagline „Wouldn’t you like to rip her to shreds?“ But imagine trying to forge a career as a tough, groundbreaking, independent-minded female artist in 1970s Nigeria. The country’s dominant artist was Fela Kuti. The crisply self-styled One Who Emanates Greatness Carries Death in His Quiver and Cannot Be Killed by Human Entity was many things – a musical genius and an unimaginably brave political rebel among them – but there were certain areas in which his zeal for fairness and justice seemed a bit lacking. He thought homosexuality was a psychological illness caused by pollution, and he thought women were „mattresses“. „An African man should not do anything called housework or cooking,“ he cheerfully told one journalist, but not everyone was as forward-thinking and progressive as that.

Into that environment charged Taiwo and Kehinde Lijadu, audibly aiming for more in life than doing Fela Kuti’s dusting. Given the prevalent climate, they were perhaps doomed to failure, but they did make a string of attitude-laden albums before moving to the US in the early 1980s. That attitude veered remarkably close to punk, via an appealingly ramshackle, untutored vocal approach, and lyrics that move from righteous political needling and calls for a riot of their own („Get out! Fight! Trouble in the streets!“ opens Orere-Elejigbo), to something far more complex and troubled. „We’re cashing in, prostitution, yeah, we’re cashing in, revolution yeah,“ they sing, brightly and blithely on Cashing In. „Poverty is still a common sight.“ It’s a cocktail of cynicism, fury and impotent despair the Sex Pistols might have recognised.

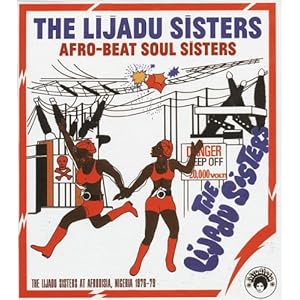

Attitude aside, what lifts Afro-Beat Soul Sisters from worthy archaeology to something genuinely thrilling is the music they made. You catch echoes of all kinds of things in their sound: a stripped-back, concise take on Kuti’s slippery funk, the insistent pulse of disco, the stinging guitars and organ of psychedelic rock, plus acoustic folk and the bassy thunder of talking drums. At its best – the mesmeric groove of Bayi L’Ense, or Life’s Gone Down Low’s defiant, super-cool strut – the music on Afro-Beat Soul Sisters is as tough as the women who made it.

They are at their least interesting when they try to make straightforward disco, because their hearts audibly aren’t in it: the vocals on Get Up and Dance cross the boundary from appealingly ramshackle and untutored to flatly out of tune.

European and American listeners who find themselves surprised by the cynicism of Cashing In – because they somehow expect African music to be intrinsically more earnest and straightforward than the rock and pop produced in New York or Los Angeles or London – might be mollified to discover that cultural preconceptions cut both ways. Disco was an infinitely adaptable genre, perfectly capable of conveying dissent. But listening to Sunshine, you get the distinct feeling the Lijuda Sisters thought disco was meaningless western pop pap, too flimsy to bear the weight of their message, and toned down their rhetoric to fit: the shift from the smartness of equating the corruption of Nigerian society with an abusive lover on Danger, to Sunshine’s facile „clap your hands and stamp your feet, be happy“ is a bit hard to take.

Still, you can’t blame them for wanting to reach a wider audience. They never did: at a time when the storecupboard of rock and pop feels pretty bare, when it feels as if everything from the past worth hearing has already been compiled in digitially remastered sound, you boggle a bit at something this good languishing in relative obscurity. What else is out there? The one certainty is it won’t be quite like this: the Lijuda Sisters still feel as singular as they must have done four decades ago.